I want to buy a new Windows 10 laptop for home use, and I want one with device encryption capability, so that the boot drive is encrypted. Until recently, this has only been possible with Windows Professional editions using BitLocker. I now see that if a laptop has the right specification, all versions of Windows 10 can have device encryption turned on.

The problem is that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to get information from mainstream laptop vendors as to whether a specific model supports device encryption. Recent MacBooks are capable of using FileVault and Apple spells out which models support it, so why is this information so hard to find for Windows laptops? Derek

I’m glad you asked because you’re right: there’s a shocking lack of information about device encryption on laptops, and this applies to Microsoft, to PC manufacturers, and to retailers. It’s also something that laptop PC reviewers rarely seem to mention, which makes it hard, if not impossible, to tell how many laptops are compatible with Windows 10’s device encryption.

And it’s not really a recent feature. Microsoft introduced device encryption with Windows 8.1 in 2013, as part of its strategy to convert Windows from a boring old desktop operating system into a mobile, always-on operating system that could run on touch-screen tablets and smartphones. It may well have been inspired by the device encryption built into Apple iPhones, which was enabled by default with the launch of iOS 8 in 2014.

Today, device encryption is a standard feature on iPhones and Android smartphones, and it was – or is – on Windows Phones. Even though Microsoft abandoned its smartphone efforts, it should be a standard feature on Windows 10 laptops as well.

Of course, PC manufacturers are driven by market demand, so it will only happen if people like us ask for device encryption, and vote with our wallets – which I’ve signally failed to do so far.

In the short term, I don’t have a good answer. You can ask manufacturers directly, which is relatively easy to do if they have online chat facilities on their websites. You can ask retailers. And if you can get your hands on a laptop in a shop, you can check it directly to see if it’s compatible with device encryption.

Consumers vs professionals

One of the underlying problems is the divide between consumer and professional users, which is reflected in the differences between Windows 10 Home and Pro.

Companies assume that consumers don’t really know what they are doing, and that consumer products should therefore “just work” out of the box. Windows 10 Home users are therefore steered into default installations that are ultimately for their own benefit. Automatic device encryption is just one of the background tasks they shouldn’t need to worry about.

By contrast, professional users are presumed to be able to cope with technical problems, even if they need a dedicated IT department to do it. Windows 10 Pro users are therefore given all sorts of configuration options, one of which is setting up BitLocker disk encryption.

I suspect the answer you will get from most PC suppliers is that if you want device encryption then you should just buy the Pro version of Windows 10, even though BitLocker isn’t really designed for consumer use. But at least it should be cheaper to do that than to upgrade Windows 10 Home to Pro by spending £119.99 online in the Windows Store.

The other alternative is to look for a free third-party solution such as VeraCrypt or AxCrypt.

Device encryption

Windows 10 displays a small padlock on the drives that are encrypted, unlocked to show that it is open and accessible to the logged in user. Photograph: Samuel Gibbs/The Guardian

Device encryption is attractive because it is completely transparent. People shouldn’t be able to tell whether they are using it or not. They don’t have to worry about their encryption key because it’s created when they log in to Windows for the first time using a Microsoft account. They don’t have to worry about saving it because the key is stored online in the OneDrive associated with their Microsoft account details.

If something goes wrong, they can use another PC to log on to their Microsoft account and download a recovery key. (A Microsoft account is usually a Microsoft email address at Hotmail or Outlook.com, though you can also use a non-Microsoft address.)

All this works well. The problem isn’t the software but the hardware requirements. To be compatible, a Windows 10 Home laptop must have UEFI SecureBoot enabled and a version 2.0 TPM (Trusted Platform Module) security chip. It also seems to require what Microsoft now calls Modern Standby, which used to be called ConnectedStandby or InstantGo. Basically, it means a device can be turned on and off like a smartphone.

According to Dell’s website, “automatic device encryption is only supported when the system … also satisfies the Modern Standby specifications” with solid-state storage (SSD or eMMC) and non-removable (soldered RAM). Which sounds like a smartphone.

Frankly, I can’t see why device encryption should depend on a power management feature or soldered memory chips, but it might explain a lack of widespread support.

BitLocker

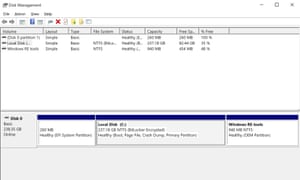

Windows 10 Home’s disk management shows the hard drive as BitLocker Encrypted. Photograph: Samuel Gibbs/The Guardian

As far as I can tell, device encryption is basically the same as BitLocker. In fact, if you have device encryption enabled on a laptop, Windows 10’s Disk Management utility says your C: drive is “BitLocker Encrypted”. The difference is that BitLocker works on lots of machines that device encryption won’t touch.

BitLocker was introduced with Windows Vista in 2006, when Windows PCs used BIOS chips to boot, instead of UEFI. It worked with the TPM 1.2 chips that were common at the time, and you could even use it without a TPM if you were willing to use a start-up key on a USB thumb drive instead. It worked on old hard drive on PCs built years before Modern Standby was invented.

In other words, BitLocker ought to work on any mainstream laptop you’re likely to buy. It may not have device encryption’s ease of use, but at least you’d get the extra security you want.

How to tell

Windows 10 Home’s device encryption simplifies securing your data, but only if your machine is compatible. Photograph: Samuel Gibbs/The Guardian

How can you find out if laptop has device encryption? It depends which version of Windows 10 it’s running.

If it’s running an old version, run the Settings app (the cogwheel icon), go to the System page and select About. There’s a section called Device Encryption at the bottom of the page, along with a button that should say “Turn off” (because it should be on).

If the About page doesn’t mention device encryption, then you can assume it’s not supported – but see below.

If it’s running a newer version of Windows 10, run the Settings app, go to the Update & Security page and select Device Encryption.

However, there is a better way to check a laptop, which is to run the old System Information desktop program. To do this, type sys in the search box on the taskbar, right click on System Information and select “Run as administrator” from the drop-down menu. Near the bottom of the System Summary page there’s an entry for Device Encryption Support. If this says “Meets prerequisites” then device encryption is supported on the hardware in question. If it doesn’t, it should tell you why not, such as InstantGo not being supported, or whatever.

Sorry to report that my 2017 Dell XPS desktop tower says: “Reasons for failed automatic device encryption: Un-allowed DMA capable bus/device(s) detected.” I must be careful not to lose it on the tube.

I don’t think anyone has compiled a list of Device Encryption Support entries for various computers, but post your results in the comments and maybe somebody will start one.

Have you got a question? Email it to Ask.Jack@theguardian.com

This article contains affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission if a reader clicks through and makes a purchase. All our journalism is independent and is in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. By clicking on an affiliate link, you accept that third-party cookies will be set. More information.

Source: The Guardian